By Zephyr

’23

Radiation is the emission of energy in the form of waves or particles. Ionising radiation (also known as radioactivity), which strips electrons from atoms and molecules it passes through, can be a major health hazard. When this penetrates living tissue, it is able to damage genes and therefore cause cancer, as the cells lose their ability to control the rate at which they replicate. Extreme levels of radiation exposure over a short period of time can even cause death within days or weeks. There are naturally occuring sources of ionising radiation, such as solar or cosmic radiation, as well as manmade sources like x-rays. Radioactive waste can also be a byproduct from nuclear reactors and fuel processing plants. Many European nations are therefore developing suitable underground repositories where this waste can be stored safely until it is no longer hazardous. Recent research suggests that biological interventions could also help tackle this problem.

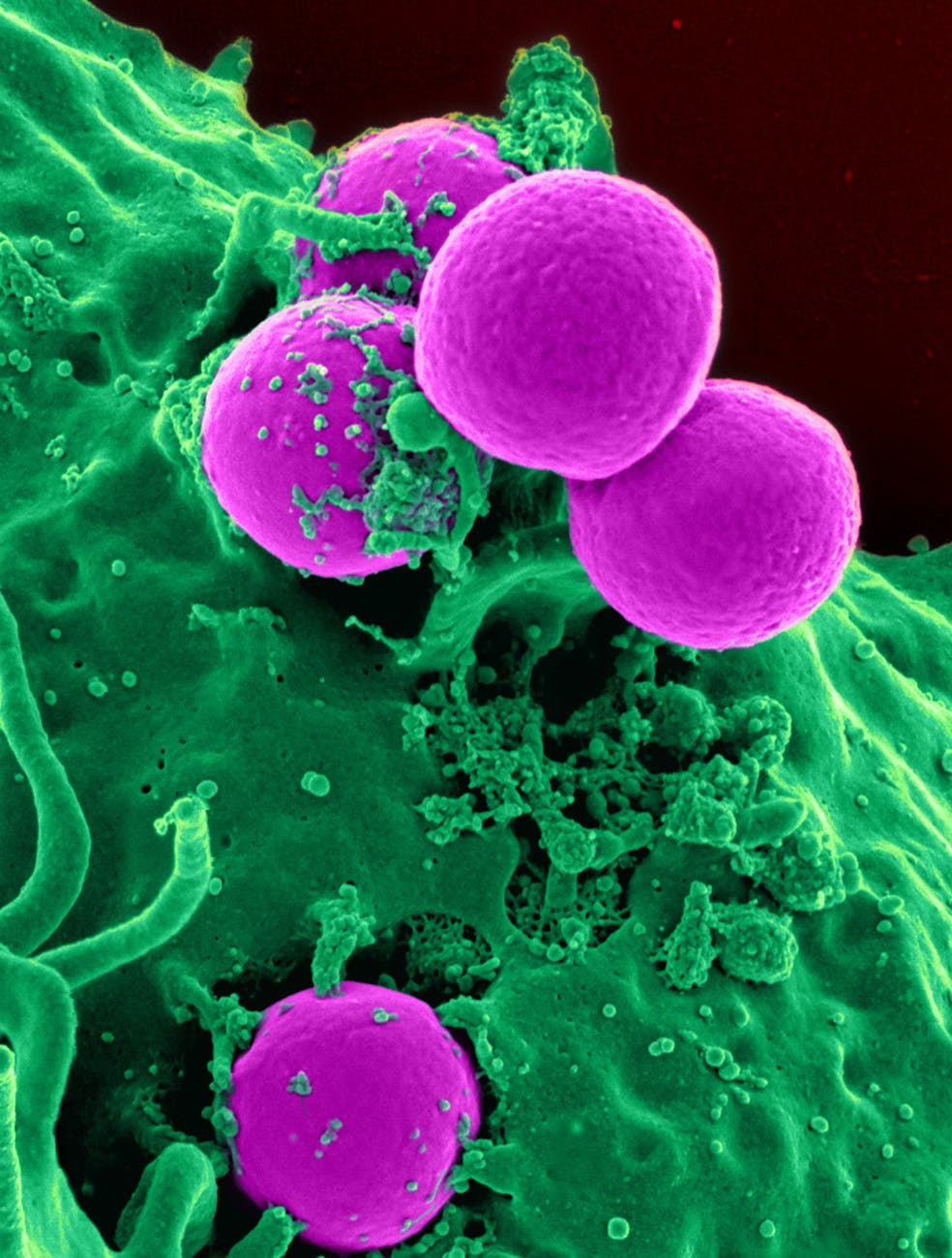

First discovered at Oregon State University in 1956, the bacterium Deinococcus Radiodurans is one of the most radiation resistant organisms known to man. Also able to thrive in environments with pH levels as high as 11, it has been termed an ‘extremophilic’ microbe.

Deinococcus Radiodurans could play an important role in improving the efficacy of radioactive waste storage because it is able to use radionuclides (radioactive isotopes) such as uranium in the place of oxygen. Some types of nuclear waste contain cellulose, an organic molecule that makes up cell walls. When cellulose breaks down under alkaline conditions, it can form isosaccharinic acid, which becomes soluble when combined with uranium. This could enable the radioactive material to seep out of a repository. Deinococcus Radiodurans uses isosaccharinic acid as a source of carbon, thereby ensuring that the radionuclides remain contained in solid form.

The way in which this extraordinary organism withstands ionising radiation could also be the key to producing less expensive and more efficient vaccines. For many years, microbiologists studying D. Radiodurans theorised that the bacterium’s strategy involved activating cellular mechanisms to protect its DNA. However, a team led by Dr. Michael Daly at the Uniformed Services University in Maryland has recently discovered that D. Radiodurans insulates key repair proteins to ensure that they are able to reverse any damage. Ionising radiation breaks apart the water molecules within a cell, triggering the formation of oxidizing compounds which can do significant damage to subcellular structures. Therefore, to protect its repair proteins, the bacterium releases an antioxidant, manganese-based compound. However, these antioxidants do not protect the bacteria’s genome from damage.

Daly believes that this principle could also be applied to viruses; Exposing the microbes to manganese antioxidants would preserve the proteins necessary for the immune system to produce antibodies against it, while preventing the virus from replicating in the body. This could significantly reduce the amount of time and money necessary to produce vaccines; Traditional vaccine development involves using genetically recombined DNA that encodes only for the proteins necessary to produce an immune response. Daly’s method greatly simplifies this process, enabling the preservation of proteins and the disabling of genetic material to happen simultaneously. Though more extensive research and development is necessary to establish whether this proposal is viable, many biologists agree that Daly’s work is promising.

Leave a comment